Description

Road-user charging is a transport-demand policy instrument. The primary environmental objective of introducing road-user charges is to discourage the use of certain classes of vehicles, fuel sources or more polluting vehicles.

As an instrument, road pricing can be tailored to specific areas, times, vehicles, emission standards and fuel types. It has the potential to generate substantial revenue, but has high investment and collection costs, for example, in the form of physical road-tolling stations or through an automated charging system that relies on complex information technology (IT) infrastructure and a good vehicle database for effective enforcement procedures. Road charging schemes have often met strong opposition and many plans have been delayed or cancelled due to disapproval from residents.

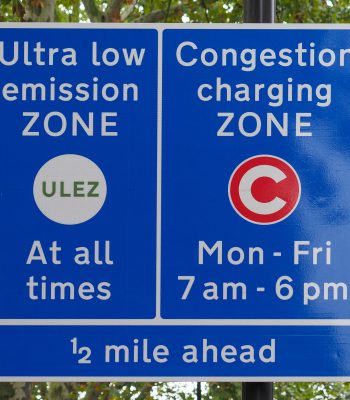

Urban road-user charging can be arranged in different ways, including through toll booths or through electronic vehicle-recognition infrastructure placed on all entry points to a targeted area of a city. Charging typically requires comprehensive upfront investment, and collection costs are substantial. Road-user charges can be tailored to specific areas of a city and to certain times of the day (for example, more expensive at peak times) and/or vehicle types (for example, fees for heavy goods vehicles). They can also be tailored to vehicle emission levels at the time of vehicle registration and are sometimes used to promote low or ultra-low emission zones.

In terms of relevant case studies, Singapore’s Electronic Road Pricing scheme was one of the first and most complex. The scheme was launched in 1998 and covers selected expressways, arterial roads and three restricted zones. The toll is applied to all vehicles and varies by time of day and direction of travel.

The London Congestion Charge was introduced in 2003 and works with a flat daily charge for driving a vehicle within the charging zone. The charge helped reduce traffic in London’s city centre by 39 per cent between 2002 and 2014. In 2019 the city launched its Ultra-Low Emission Zone, which includes more stringent emissions standards.

Stockholm’s congestion charge was introduced in 2006 and is designed as a barrier scheme, in which a payment is required for each entry through the barrier, and is dependent on the time of day. A study of congestion pricing in Stockholm between 2006 and 2010 found that in the absence of congestion

pricing, Stockholm’s “air would have been five to ten percent more polluted between 2006 and 2010, and young children would have suffered 45 percent more asthma attacks”.[1]

Resource implications and key requirements

While there is no clear-cut way of narrowing down the resources needed to introduce a road-pricing measure, it is generally a costly solution that requires strong administrative capacity. It may require complex IT infrastructure, a good vehicle database for enforcement and significant changes to legal and organisational frameworks. For example, in 2015, Transport for London’s collection cost was £85 million, representing one-third of total fee collection – with a congestion charge of £11.50 per day.

In cities where no dependable licence plate database exists and there is no legislation enabling congestion charging, this step might be the greatest bottleneck in the entire process. The relationship between the national legislative framework and regional or city legislative structures is also important in that cities or regional areas may be able to enact their own laws, or they may have to rely on national laws being applied in their geographical areas.

Implementation obstacles and solutions

Despite evidence of impact, the public has repeatedly rejected proposed road-user charges. For example, in Manchester and New York in 2008, and Copenhagen in 2012, tolling schemes were rejected by public referendums. Public acceptability requires an incremental introduction of fee levels. It also requires consultation and feedback from the public in designing the policy, and robust awareness campaigns, with evidence of improvement in terms of traffic congestion, public transport and road networks.[2] Furthermore, the vision of the policy should be part of an overall traffic plan, including improvements in public transport funded by the road pricing revenue. In London and Oslo, resistance to congestion and toll charges was partly overcome by transparently linking these fees with public investment.

Comprehensive congestion charging remains suitable for large cities with a congestion problem in their city centres, but is rarely a recommended solution for small to medium-sized cities due to the administrative and financial burden. For small to medium-sized cities, parking measures are much more effective, but may need to be combined with charges for goods vehicles.

Comparison with other policy options

Effective use of restrictive parking policies has many of the same benefits as road-user charges. However, parking policies are often significantly easier to implement and can be introduced in a more gradual fashion.

References

[1] N. Rogers (2017), “Driving Fee Rolls Back Asthma Attacks in Stockholm”, Inside Science website, February 2017.

[2] P. Collier, E. Glaser, A. Venables, M. Blake and P. Manwaring (2019), “Access to opportunity: policy decisions for enhancing urban mobility”, IGC Cities that Work Policy Framing Paper.