Context and policy overview

Since the early 2000s, South Korea has been forging a new concept of the Ubiquitous City (u-City),[1] whereby widely dispersed sensors, connected devices and internet technologies enable cities to gather valuable data, create new services and upgrade existing services, ushering in an era of the intelligence-based society.

In 2006, the national government proposed a u-Korea (Ubiquitous Korea) strategy, divided into (1) a development stage (2006-10) and (2) a mature stage (2011-15). The key tasks from 2006 to 2010 were the completion of the construction of the ubiquitous network infrastructure, the development of regulation, the application of IT technology and the establishment of a u-oriented social system. The aim from 2011 to 2015 was to expand u-based services to improve government efficiency, create new opportunities for local businesses and enhance the quality of citizens’ lives.

In the process of promoting the u-Korea policy, the Ministry of Information and Communication (MIC) also successively launched several u-IT core plans, one of which was the comprehensive u-City plan, which brought smart city construction into the national strategy.

In line with the national strategy, the Busan government adopted a cloud-based infrastructure, collaborating with Cisco and South Korea’s leading telecom operator, KT, to build a more cost-effective Green u-City[2] – an ICT infrastructure-based green growth initiatives. It hoped to transform physical communities into online ones by using the network as the platform for more efficient city government planning and management and for information collection, processing and sharing in real time.

The city integrated several systems to provide everyday public services over an internet-enabled cloud infrastructure, supported by open innovation that also generated new opportunities for local business, thus stimulating job and economic growth.[3] It also tackled the growing costs of increased data storage and processing requirements as public services moved online.[4]

Implementation

Stage 1. Busan u-City plan phase 1 (2006-11)[5]

Busan began its u-City programme in 2006, focussing on designing and retrofitting new-generation technology into the city’s major infrastructure, such as the ports, transportation, and tourism. As public digital services expanded, Busan also needed a more efficient way to manage the growing amount of data and to control increasing operating costs. This was where the cloud infrastructure came into play. Cloud-based city services streamlined data collection and allowed both public and private communities to share and access information.

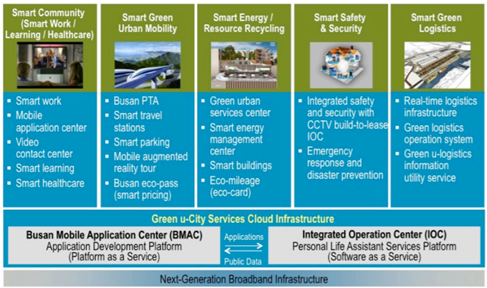

The Busan government brought in partners from the private sector to construct the cloud. Public-private partnerships were forged with KT (formerly Korea Telecom), which provided an integrated platform, and Cisco, which was responsible for middleware solutions. Its cloud architecture was built upon solid networks, fault-tolerant data centres and ubiquitous internet reach to support the instant deployment of intelligent services. The blueprint and business architecture of the Busan Green u-City was in four broad layers (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Busan Green u-City Blueprint

Source: Cisco IBSG (2011)[6]

Source: Cisco IBSG (2011)[6]

The top layer developed the city’s long-term objectives in five key areas of urban policymaking: urban mobility, environment, utility services, security and safety, and community and public life. The second layer encapsulated the vast array of services provided in each of these categories. The third consisted of the cloud infrastructure that enabled the Green u-City services. Most importantly, all the layers were supported by a robust 10GB citywide broadband infrastructure introduced in the early stages of city development.

In 2010, a shared application development platform, the Busan Mobile Application Centre (BMAC), was launched to gather city administration and developers together in utilising open city data to raise public services to the next level.[7] The BMAC and Integrated Operation Centre (IOC) were the heart of Busan’s Green u-City Services cloud infrastructure. The former was an app development incubator that provided open city data, while the latter managed all the city data to help decision-makers make better city management and planning decisions.

- Busan Mobile Application Centre (BMAC)

The BMAC – later renamed the Busan Mobile Artificial Intelligence (AI) Centre – was established by the Busan IT Promotion Agency and funded by the city government. It helped local businesses and developers to design and launch public-service mobile apps. Virtual tools and software, as well as training and technical support, were offered, which helped cover the expensive upfront costs of app development. The BMAC rolled out the following measures to support its members:[8]

- computer operating systems and electronic devices for entrepreneurs to experiment and demonstrate their ideas

- consulting services, online and physical meeting rooms to facilitate the exchange of information between stakeholders, including enterprises, developers and academics

- access to a database that aggregated user data on various public services.

These measures allowed businesses to identify citizens’ unmet needs and to propose marketable solutions. All apps developed on the BMAC platform would go through trials and, when deemed mature, be relocated to more advanced work centres to prepare for launch.[9]

- Integrated Operations Centre (IOC)

The purpose of the IOC is to scale up and improve Busan’s cloud infrastructure. Its responsibility is to collect, store and manage the various data collected through the city’s smart devices, such as sensors, surveillance cameras and smart meters on public services like buses and the disaster prevention system.[10] As a single storage system for all types of data, the IOC also plays a vital role in analysing and processing data so that it can be widely shared among city departments and used to form meaningful insights.

One example is connecting the CCTV network with the IOC, so that municipal departments can share information and communicate instantly, regardless of their physical location. This has helped to reduce the crime rate in certain neighbourhoods by 31 percent and lowered operating costs by KRW 744.4 billion (US$ 676.7 million).[11]

The IOC’s public-service database is open to BMAC member businesses and these companies can launch their applications on the IOC, offering them free to citizens through any internet-connected device. The openness of data has also encouraged private companies to collaborate with government agencies. This healthy ecosystem has enabled the city government to transform certain services into free public services.[12]

Stage 2. Busan ubiquitous city plan (2012-16)[13]

In 2012, Busan started the second phase of the u-City plan to support its continued growth to promote a smart economy, life, culture, and greener city, focussing on service trials and the development of key platforms for content management. The city government rolled out more than 35 digital services across eight sectors: transport, tourism, health, ports, disaster mitigation, education, an integrated management centre and the environment.[14] Services included electronic tracking tags on vehicles, electronic tolls, real-time bus information systems and CCTV networks. [15]

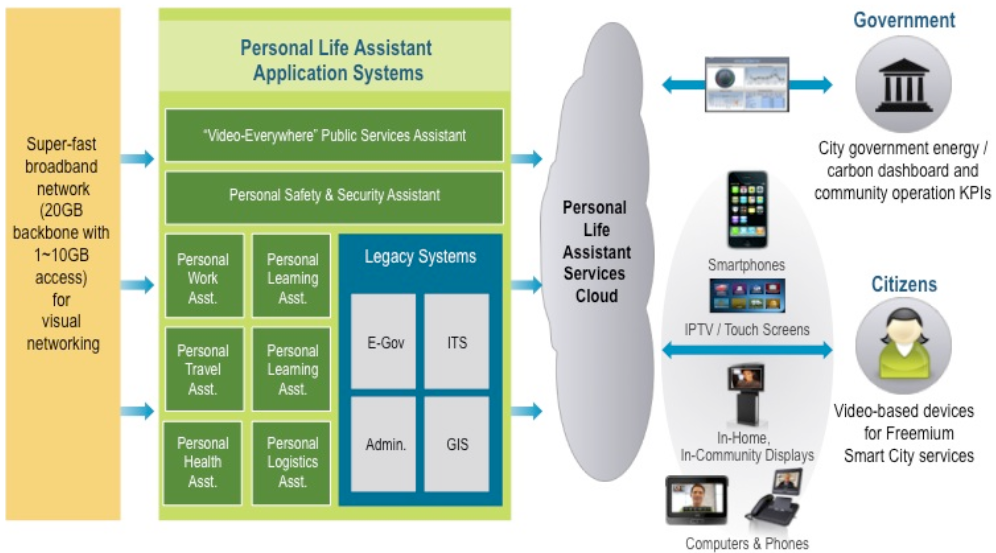

Figure 2. PLA smart city service on network-enabled cloud infrastructure.

Source: Cisco IBSG (2011)[16]

Source: Cisco IBSG (2011)[16]

- Personal life-assistant services platform (PLA services)

The applications offered on the IOC encompass a wide range of free, eco-friendly services, known as PLA services (Figure 2), aimed at improving people’s travel and living experience, among other things. For example:[17]

- Citizens can reserve workspaces at nearby work centres through electronic devices, for example, public workspaces equipped for teleconferencing and remote working facilities.

- A personal travel assistant allows users to access real-time public transport information, plan the most efficient route to their destination and calculate how public transport reduces their carbon footprint.

- A personal energy assistant shows people living in smart buildings near-real-time information on their gas and electricity consumption. Residents can estimate their carbon footprint based on the type of neighbourhood they live in and adapt their ways of living based on the energy assistant’s suggestions.

By facilitating the creation of different public services that focus on the idea of “green,” the IOC has helped to incentivise citizens to opt for a more sustainable lifestyle, contributing to the achievement of the forthcoming green city plan.

Stage 3. Smart city (2016-present)

Through its cloud infrastructure and improved broadband system, Busan was able to form a solid foundation for its long-term plans to become a greener and smarter city. The municipal government aimed to use data stored in the IOC and upgrade existing smart services for broader purposes, such as urban mobility, port management, air quality monitoring and farmland and crop management.[18]

Busan’s advanced port management system, for instance,[19] includes a real-time monitoring system to collect data on the environmental impact of ships and trucks, as well as drones to monitor the level of fine-dust pollution at the city’s port. The air quality monitoring system[20] was developed to monitor air pollutants at monitoring stations and collect data from sensors installed on buses, allowing citizens to access real-time information on air quality on their phones.

Barriers and factors critical to success

The city government encountered financial barriers in transforming Busan into a green smart city. In the first few years, national and city government subsidies were the main sources of funding. The lack of a profitable business model became a major challenge when subsidies stopped, as the city could not recoup the operating costs of its smart services. However, the city overcame the barrier by bringing in private partners. Combining investments from Cisco and KT, a total of US$ 452 million was put into Busan’s u-city plan.[21]

Well-developed broadband has contributed to Busan’s success in building its cloud infrastructure. The city government realised early on that broadband was the cornerstone of all smart services. It completed the broadband infrastructure before rolling out extensive smart services, minimising the risk of unstable data transmission.

The development approach for Busan’s smart city strategy also contributed to its success. Rather than develop different smart services at random, the city government adopted a comprehensive strategy that focused on creating a smart-city ecosystem, developing each layer incrementally.

Results and lessons learned

The cloud infrastructure showed great potential for creating a new revenue stream. In its first year, the BMAC reaped more than US$ 2.2 million in profit and dividends from supporting app development, plus online sales revenue US$ 42,000 for Busan City.[22] During that period, BMAC helped to establish 13 companies, while local start-ups launched 70 mobile apps.[23] The city government aims to employ 3,500 more app developers in the coming years. Government officials also benefited from better data management, improving city resources and streamlining operations. The city was estimated to have reduced its carbon emissions by 2,981 metric tonnes annually as of 2020. Put differently, Busan now emits nearly 68 per cent less CO2 than other South Korean cities without green urban services.[24]

Cities interested in developing a cloud infrastructure can learn from Busan’s experience:

- Opening up city data to the public and to companies is a way of joining publicly owned resources with corporate expertise, enabling the provision of value-added services.

- The operation of cloud infrastructure entails many factors, including connectivity, financial resources and stakeholder engagement. Cities need to assess their technical readiness and financial and institutional capacity before implementing such a broad-based plan.

- Appealing incentives encourage businesses to improve public services. In the case of Busan, small and medium-sized companies who signed up to the BMAC received subsidies for developing apps, boosting competition to join the BMAC.

- Developing a smart city can be a long-term investment and needs to be supported by a viable business model. The Busan City government provided the cloud that helped local businesses create value-added public services, the profits of which were partly invested back into the city through partnerships with private companies.

Links to similar initiatives

- Bucharest, Romania: cloud-based services

- Jaipur, India: connected digital platform

- Copenhagen, Denmark: digital solutions to reduce carbon emissions