Context and policy overview

As an economic hub and academic stronghold, the City of Chicago has long stood out for its use of data in the design of public policy. Most notably, in 2011, Mayor Rahm Emanuel and his team spearheaded an Open Data Initiative that sought to publicise data, covering practically all aspects of municipal decision-making.

Still suffering from the global financial crisis, Mayor Emanuel saw the opportunities of open data in terms of increasing innovation and civic engagement. By inviting civil society and the business community into the decision-making process, Mayor Emanuel could simultaneously face two of his most important challenges: (1) the clear need to promote broad-based economic growth and (2) a competing requirement to tackle the growing budget deficit.[1]

To this end, Mayor Emanuel’s administration published various types of government datasets – such as building-permits, budget records, financial statements and spending plans – as a means of coordinating expectations and unlocking the power of information for business and investment decisions.[2]

Today, the Chicago Data Portal provides open access to more than 600 datasets and stands as a prime example of how to use open data to improve urban life.[3] At the government level, Chicago has developed analytical tools, such as the SmartData platform, which allows predictive problem solving across sectors such as public health, homelessness, infrastructure maintenance and the delivery of core services.[4] At the same time, the business and research community has successfully launched more than 30 website applications in areas from food and beverages to transport, construction and schooling. Such examples demonstrate the tremendous power of the private sector to innovate on delivering vital public services.

Implementation

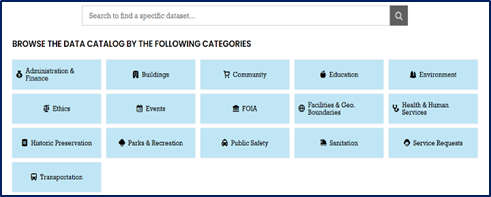

The Chicago Data Portal has become the city’s primary means of bringing open data to the public. Since its launch in 2011, there has been a 60-fold increase in the number of datasets it hosts, on topics ranging from administration and health services to transportation, public safety and open spaces (Figure 1). As a core part of its objectives, the municipal government has aimed to make the portal as transparent and accessible as possible. Anyone who is eager to improve public life, or simply curious about how the city works, can easily log in and access information, thus maximising interactions with the website as well as the value of the data.

Figure 1. Chicago Data Portal

Source: Chicago Data Portal[5]

The real success of Chicago’s open data initiative had to transcend the portal itself, however. What really made the programme successful was that the government extended it into a wider strategy on its organisation framework and technical capabilities.

Organisational framework

Nearly a year after the launch of the Data Portal, Mayor Emanuel issued an executive order that formalised the structures and processes for developing the open-data initiative. The order set out the following changes:[6], [7]

- The city’s Department of Innovation and Technology (DoIT) was tasked with spearheading inter-agency collaboration and with running the actual Chicago Data Portal.

- A chief data officer (CDO) and a chief information officer (CIO) were appointed to coordinate implementation, compliance and expansion of the city’s open-data policy. The CIO is mostly responsible for creating business value from datasets and information technology (IT) resources, while the CDO has operational responsibility.

- An Open Data Advisory Group was established, chaired by the CDO, comprising the open-data coordinators. It assists the DoIT in writing an annual compliance report, setting out each municipal agency’s implementation plan, timeline and review process for releasing municipal data.

- Lastly, to ensure all agencies regularly maintain and update their public data, the city appointed an open-data coordinator in each municipal agency, whose role was to allocate tasks associated with open-data initiatives and to liaise with all departments overseeing implementation.

These changes to the government’s organisational structure played an important role in reinforcing the city’s commitment to data openness and in clarifying the responsibilities of all parties involved. Moreover, they helped boost the sustainability of the initiative, helping to secure its use beyond Mayor Emanuel’s tenure, which ended in 2019.

Following these changes, the CDO pushed for two other important reforms: (1) for the consolidation of city IT services and (2) for the use of digital techniques such as artificial intelligence (AI) and predictive analytics in decision-making.[8] Consolidating Chicago’s IT services was the first step in enhancing the efficiency of the city administration. Like most big cities, Chicago’s governmental departments tended to work in silos; each department worked with separate data types and standards, with many operations isolated from their counterparts. Breaking down these siloes required the city to move its various existing computer systems, including the emails and applications of about 30,000 employees, to a singular, harmonised cloud operating system. This streamlined the city’s data management, saving Chicago’s taxpayers US$ 400,000 annually in staff time and resources.[9] In addition, data became easily accessible when stored in a shared place, lowering the barriers to data mining and analysis[10] – a key enabler in the development of predictive tools. In terms of budget, personnel costs (including adequate staffing and training) and the cost of contracting a data-solutions provider to operate and maintain the portal were the two major areas of fund spending.

Technical capacity building

To effectively design and operate the open data portal, the Chicago administration had to ensure sufficient technical support for platform maintenance and optimisation. Federal governments typically have sufficient technical capacity to operate and maintain systems themselves, however, in the case of municipalities such as Chicago, such an undertaking often requires improvements to staffing or external support.

In Chicago’s case, the municipality chose Socrata as a platform supplier for the Data Portal, as it was one of the most established companies in the field.[11] Socrata developed a platform for the city, whereby data were provided in proprietary and open-source formats and supported whenever technical issues arose. This helped the government to avoid over-stretching its internal IT resources.

Two types of user licence were issued. The general user licence allowed the public to retrieve data through the Chicago Data Portal. Under its terms and conditions, the city administration owned the data, reserved the rights on how to remove them from the portal and restricted how they could be used. As the release of public data was an ongoing process, users were encouraged to suggest which datasets should be added to the portal and these suggestions were reviewed regularly.[12]

The second, more business-friendly licence was published on the city’s GitHub,[13] a worldwide platform on which developers manage their source-code changes. On the GitHub, the developer community could examine the datasets, propose edits and detect errors.[14] Instead of developing civic apps itself, the city government encouraged the civic developer community and private entrepreneurship to use datasets for app development.

Barriers and factors critical to success

When launching an open-data initiative, cities often encounter challenges resulting from their organisational structure and technical framework and, therefore, see low stakeholder participation. In Chicago, restructuring the organisational framework of municipal agencies was the initial step in its successful development of open data, which needed strong leadership as a foundation.

- Leadership

First, while the DoIT was empowered to coordinate all of the agencies involved, each agency appointed an internal data coordinator to allocate tasks and serve as contact point. This mitigated jurisdictional conflicts and low staff commitment due to heavy workloads. Second, the Mayor assigned a CDO and a CIO, who worked within the DoIT, to oversee the open-data initiative’s implementation and promotion. Not only were they tech experts who helped the city government to choose and develop suitable technical solutions, they also exercised strong leadership in communicating with municipal agencies, the public, businesses, academia and the media.

- Stakeholder engagement

Robust stakeholder engagement was a key driver of Chicago’s open-data development. Prior to the Mayor’s executive order, Chicago’s open-data community and universities had advocated for increased public data openness as a means of supporting public policymaking and social programmes.[15] This early adoption established an ecosystem enabling the city government and civil society to encourage developers to use public data and to bring open data into Chicagoans’ daily lives.

- Community

Through a partnership with the National Organisation Code for America on the Open 311 project,[16], [17] Chicagoans could, for example, request services, review construction sites in their neighbourhood and report issues via the internet or text. The status of submitted requests could be easily tracked on the official website. Open 311 was more than an upgraded hotline service; it was also a source of data. Citizens could use the amassed requests, photos and data on the Chicago Data Portal to develop civic apps and web pages.[18] For example, a high-school student could take the data and build an app pinpointing the location of parks relative to schools.

The city government also collaborated with the Smart Chicago Collaborative, a local organisation, to arrange regular meetups, dubbed OpenGov, where the public, tech developers and government employees could discuss possibilities for real-life uses of open data.[19] Nearly 50 meetings have taken place to date, with discussions spanning an array of subjects, from law and justice to open government and civic innovation.

- Business and media

The CDO was tasked with meeting regularly with entrepreneurs and developers who wished to create civic apps. This forged an opportunity for the city to understand how private companies transformed data into value-added products. The city government has also provided software tools for developers and constantly updated its API’s.[20] This ensured that the private sector remained active users of the city’s data.

The Chicago Data Portal has become a reliable source of information for local media, such as the Chicago Tribune and the Sun-Times.[21] The city government actively promoted its open-data initiative in media interviews and at public events to demonstrate its openness as to suggestions of which datasets should be given priority. This communication turned public criticism into constructive discussions while any errors or issues in data were being discovered.[22]

- Academia

Partnerships with the academic community also enabled the city to put its wealth of data to practical use. The city administration collaborated with the University of Chicago and Carnegie Mellon University, which helped to create the SmartData platform, a predictive analytics platform, and Chicago’s Data Dictionary, a database for metadata.[23]

The SmartData platform, launched in 2013, aggregated and analysed data to help city leaders make more informed decisions. One innovative feature was its predictive analytics. For example, the platform collected data on traffic patterns and pedestrian activity in one area of the city, then analysed them in the context of other municipal data, such as weather patterns, traffic signals and streetlight access.[24] This allowed city departments to predict when they might need to intervene to prevent traffic accidents.

Chicago’s Data Dictionary displayed all of the metadata for each dataset.[25] While the Data Portal provided actual datasets, the Data Dictionary created a map of all databases in the city. The Data Dictionary was a cornerstone of full transparency of city data, as well as a tool to help city staff and external stakeholders better analyse the myriad lines of data available.

Results and lesson learned

By 2020, the Chicago Data Portal had published more than 600 datasets covering a wide variety of subjects. Some of the most widely used datasets include crime reports, food security and lists of government employment structures and working models. Cumulatively, these datasets have been viewed and downloaded more than 16 million times.[26] Such datasets ‒ and the portal itself ‒ have been used to tackle numerous public policy challenges, from food security and public health to pest control, transportation and education. Another major benefit of the open-data initiative is that it has improved the operational efficiency of city personnel, reducing their workload related to data collection and analysis and freeing up more time to pursue new policies. For example, as more and more datasets have been released, requests for public information have declined by around 50 per cent.[27]

By providing open public data, Chicago also experienced a boom in its tech community: more than 30 civic apps have been created and launched with the city government’s support. Some of them have turned into successful start-up companies, including SpotHero, a hackathon-winning app that helps users find and reserve parking spaces.

Other cities interested in establishing open data can thus learn from a number of Chicago’s experiences:

- A supportive organisational structure is fundamental to developing a sustainable open-data system. Crucial steps can include the appointment of dedicated officials, the clarification of agency roles and the fostering of collaboration between the agencies involved.

- It is important that the mayor underpin the initiative with their executive power. In the case of Chicago, the city administration could only broaden the scope of the open-data initiative after the 2012 executive order was issued.

- Opening up public data lays the groundwork for a city’s digital economy. As seen in Chicago, unleashing the potential of published data encourages the development of advanced tech tools and apps.

- Engaging stakeholders is an indispensable element in Chicago’s success. To encourage participation, the city government incorporated open data into the 311 services, formed positive relationships with multiple communities and acted on the suggestions of the public.